The Neuropsychology of the Reckless Litigator:

An Essay Containing Plausible Hypotheses

A Win Before Trial whitepaper on the problem of

impulsive and reckless decision making in litigation.

© 2010 Michael Palmer, Win Before Trial.

Contact Mike Palmer at 802 870 3450 or

[email protected] for permission to reprint this article.

impulsive and reckless decision making in litigation.

© 2010 Michael Palmer, Win Before Trial.

Contact Mike Palmer at 802 870 3450 or

[email protected] for permission to reprint this article.

By Michael Palmer, J.D., Ph.D.

Executive summary: A significant percentage of lawyers reject sensible settlement proposals, preferring trial with financially worse outcomes. This essay posits the hypothesis that the reckless litigator phenomenon is caused, at least in part, by aberrations in the neuro-physiology of the reckless litigator's brain in conjunction with four established cognitive biases and intuitive shortcuts and the male tendency to contend when rank and status are not defined by social roles. The ethical implications of the reckless litigator syndrome are addressed, and strategic and analytical thinking independent of the reckless litigator's behavior are proposed as potentially effective responses.

A few months ago, a friend told me about a lawsuit in which the plaintiff’s attorney demanded $500,000 to settle even though both the law and the evidence were totally against him. He would not budge. Because the negotiations were at an impasse, the case eventually went to trial, resulting in an ignominious defeat for the plaintiff. My friend asked me why this kind of thing happens and what can be done about it. This essay is my effort to answer the first part of the question and to suggest what to do when you’re on the other side.

The Problem: Chasing Longshots

Over 95% of all lawsuits are resolved by agreement—before any verdict is rendered; but with hundreds of thousands of lawsuits pending at any given moment, tens of thousands of trials occur in state and federal courts every year. Recent research by Randall Kiser and others.[1] provides conclusive evidence that many parties erroneously reject settlement proposals, obtaining significantly worse results at trial, but nevertheless convincing themselves that it was something other than their own decision or incompetence that led to the disastrous outcome.[2]

Consider the following stories:

In 1949, Nick “the Greek” Dandalos and Johnny Moss sat down to a game of five-card stud at Binion’s Horseshoe in Las Vegas. In one legendary hand, Dandalos bet $50,000 on the chance—less than 7%—of drawing a Jack as his last card, which, amazingly, he did. Having computed the odds against the Greek’s having a Jack in the hole, Moss shoved in another $200,000 only to learn that his opponent had lucked out. The Greek won $250,000 in that one hand. When the game ended after several months of ‘round-the-clock play, however, Moss walked away with over $2.5 million of the Greek’s money. As Moss later put it, he had “figured the Greek for a chaser—playing hunches instead of the cards—and he used that insight to drain the Greek’s bankroll.”[3]

Shortly after becoming general manager of futures markets at Barings Bank in 1992, Nick Leeson began making unauthorized speculative trades in large amounts. At first, these trades went well, earning the bank significant profits and Leeson substantial bonuses. When the trades started failing, Leeson at first used an error account to hide his losses, which came to over £2 million. By the end of 1994, the losses exceeded £204 million. When Leeson fled Singapore in February of the following year, the losses had climbed to £827 million, twice the bank’s trading capital, a loss large enough to bring down the oldest merchant bank in London (1762 to 1995).[4]

In February 1994, eight members of a rescue team, having just saved three adventurers in Pincher Creek (Canada), were on their way back to home base when one of their number challenged Lane McGlynn to a game of hammer-heading, a race to see who can reach the highest point of the mountain on his snowmobile. Knowing the dangers of an avalanche in this area, the commander of the rescue team had expressly prohibited any hammer-heading before he sent the team on its rescue mission. Nevertheless, 21-year old McGlynn took off almost instantly upon hearing the dare. After his snowmobile came to a halt, the other party to the bet followed, presumably wanting to see if he could make it further up the hill. Shortly after he started, however, the snow broke loose, starting a massive avalanche, which eventually killed McGlynn and one other rescuer who was unable to start his snowmobile in time to get out of the way.[5]

A little over three weeks were left before the scheduled beginning of the trial of Anderson et al. v. Cryovac et al., the Woburn, Massachusetts toxic tort case made famous in A Civil Action. The judge having urged the parties to get serious about settlement, Jan Schlichtmann and his partners decided to demand $175 million, hoping to end the haggling at around $100 million. The lawyers gathered in an opulent conference room at the Boston Four Seasons for the settlement showdown. After Schlichtmann finished his introductory remarks, James Gordon, the firm’s financial advisor, laid out the plaintiffs’ demand: $1.5 million for each of the eight plaintiffs for 30 years plus $25 million cash now plus another $25 million to establish a foundation to study toxic poisoning through groundwater pollution—altogether, $410,000,000. Jerry Facher, representing Beatrice Foods, remarked, “If I wasn’t being polite, I’d tell you what you could do with this demand.” After Schlichtmann answered a few questions from Bill Cheeseman, the lead attorney for W.R. Grace, Facher packed up his brief case, stuffed a croissant in his pocket, and walked out. Cheeseman and his team quickly followed. The entire negotiation had lasted 37 minutes. The case went to trial, and Schlichtmann ultimately declared bankruptcy.[6]

And then there was the defense team in John Edwards’s last big case, Lakey v. Sta-Rite, involving a young plaintiff who would need continual medical care and numerous surgeries during much, if not all, of her remaining life. Shortly before trial, after all other defendants had settled for slightly more than $5 million, Sta-Rite rejected the plaintiffs’ settlement demand of $4.7 million, offering only $100,000. Three weeks later, the jury returned a $25 million verdict in compensatory damages alone with the punitive damages phase yet to come. At this point, Sta-Rite agreed to settle for the jury verdict.[7]

These stories (and others that could be added from auditing, medicine, and other fields) have one thing in common: The principal players acted impulsively, taking chances a rational analysis would reveal as foolhardy.[8] Nick the Greek bet over $50,000 (in 1949!) on the 7% chance that a Jack would turn up on his last card. The snowmobilers risked triggering an avalanche after having been ordered not to do any hammer-heading. Schlichtmann let unadulterated avarice mixed with a heavy dose of moral outrage cloud his thinking to an extent that he blew up any chance of a pre-trial settlement. (Facher and Cheeseman were not behaving in the most rationally responsible way either.) And the defense in the Sta-Rite case bet its $22.5 million insurance policy that John Edwards, who had racked up $125,000,000 in settlements and verdicts in the 15 previous years, didn’t know what he was doing.

The phenomenon on display in all of these examples was dramatized in the movie, Tin Cup. The protagonist (Tin Cup), a golfer with superb technique who ekes out a living as a driving range pro, needlessly takes risky chances in important games. Self-control eludes him. In the climax of the movie, Tin Cup blows his chance to win the U.S. Open by repeatedly and unnecessarily trying to hit a 250 yard shot with a 3 wood over water onto a postage-stamp green, finally succeeding—and scoring a 12 on the hole.

What is going on when lawyers throw caution to the wind, refusing reasonable buyouts and going for broke on the longest of long shots? What explains the “reckless litigator?” Among the many possible explanations for this kind of behavior, a few candidates derived from neurology and cognitive science merit particular attention, providing clues about why the reckless litigator—notwithstanding his fiduciary duty to his client—poses a special challenge to a rational adversary.

The Diagnosis—“The Fault, Dear Brutus . . .”

There are many possible explanations of the reckless litigator syndrome (reckless gambler, reckless skier, reckless golfer, etc.), the most obvious being simply that the lawyer does not have a good grasp of the law or evidence or both respecting the case at hand. While that theory would explain some negotiation decision errors, i.e., the failure to properly assess the value of the case based on probable outcomes, it would not cover all instances of negotiation decision errors in the settlement context. As Jan Schlichtmann’s settlement decisions in A Civil Action illustrate, some highly competent lawyers—lawyers who know the law inside out and are thoroughly immersed in the evidence—behave recklessly in high-stakes bargaining contexts.

Research on cognitive biases and heuristics together with recent developments in the field of Neureconomics suggest that at least part of the “fault, dear Brutus, lies in ourselves” or, more accurately, in the neurophysiological makeup of the reckless litigator's brain. The following discussion summarizes some of the results of this research as it applies to the reckless litigator phenomenon.[9]

Hopped Up on Dopamine, Serotonin, and Testosterone

Extrapolating from the extensive research on loss aversion,[10] we can assume that given the choice between accepting a settlement proposal of $200,000 and proceeding to trial with a 1/3 chance of winning $600,000 (and a 2/3 chance of nothing), about 70-80% of us will take the $200,000. Much of the scholarly discussion on loss aversion focuses on the choice that most of us--the 70-80%--make. We choose to avoid losses. But some of us—including reckless litigators—take the other path. We go for it. We engage in risk-seeking behavior. “Hey, a 1/3 chance at $600,000 sounds like a pretty good deal.”

This predisposition to risk-seeking is further buttressed in the settlement context by the endowment effect—our tendency to demand more when we sell an object than we would pay if we were buying it.[11] In the settlement context, we value the same case more if we are the seller (plaintiff) than if we are the buyer (defendant).[12]

As the seller, the plaintiff sees the case as having much greater value than does the buyer/defendant. The endowment effect creates a natural gap between plaintiff and defendant that must somehow be bridged.

But this effect is exacerbated with the reckless litigator, who harbors a subconscious need to go for it, much like Nick Dandalos, Nick Leeson, and the movie character Tin Cup.

Now comes a gaggle of scientists who are establishing a correlation between loss aversion/risk seeking and the genetic structure of our neurotransmitter systems. For example, the authors of one recently published study provide evidence that the amount of dopamine present in certain areas of the brain modulates the sensitivity towards the valuation of gains while the level of serotonin modulates the sensitivity towards valuation of losses.[13]

To function well, we need dopamine, for which our brains have special receptors called dopamine receptor genes. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that carries impulses between nerve cells, promoting increased feelings of alertness, wakefulness, assertiveness, and aggressiveness.[14] It is part of the brain’s reward system, helping to create the positive effects that various objects or conditions (food, sexual contact, warmth, drugs, etc.) have on the individual.[15]

Most of us have four repetitions (alleles) of the receptor gene D4 (DRD4), which means that we don’t need all that much dopamine to get the job done. A little goes a long way. Some of us (the percentage varies by population) have seven alleles of D4, commonly referred to as DRD4.7. Those people need more dopamine to get the same effect that the standard D4’s get with less.

A considerable body of research has established a correlation between the dopamine receptor D4.7 (the long form of D4) and risk-seeking behavior. Apparently, such activity stimulates the increased production of dopamine that D4.7’s need for brain processes that control a variety of functions, including the ability to experience pain and pleasure. Researchers have established correlations between D4.7 and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder,[16] pathological gambling,[17] behavioral disinhibition,[18] financial risk taking in men,[19] alcoholism,[20] early sexual activity,[21] impulsivity,[22] and long-range migration.[23]

Related research has looked at the correlation of long forms of serotonin receptor genes with risk-related behavior.[24]

A recent study found that repeat functional polymorphism in the Monoamine Oxidase A Gene is associated with a preference for long-shot lotteries and reduced purchasing of insurance—the behavior profile of the reckless litigator.[25] Like the studies of dopamine and serotonin, the risk-seeking behavior correlates with an unusual (long) form of the gene.

And, of course, there is also the testosterone factor, which is why I’ve been using the pronoun “he” when referring to the reckless litigator. Several researchers have found a correlation between testosterone levels and risk-seeking behavior.[26] One study of risk taking on a London trading floor found that a trader’s morning testosterone level predicts his day’s profitability, and the persistence of acutely elevated steroids may shift risk preferences, affecting a trader’s ability to engage in rational choices.[27]

Scientists and scholars in the emerging field of Neureconomics[28] are pulling these and other findings about brain function together into theories about risk aversion and atypical risk-seeking (a/k/a novelty seeking) that are augmenting and enhancing Prospect Theory, which is a cornerstone of behavioral economics and contrasts with classical expected utility theory.[29]

Playing the game is more neurochemically rewarding than winning. Put differently, the reckless litigator needs the increased risk to generate the amount of dopamine/serotonin that most of us get from less risky behavior, just as a person with impaired hearing must turn up the volume to hear what others hear at lower volume.

There is a paradox related to the Reckless Litigator Syndrome. If we think of him as impulsive, then we would expect that he is predisposed to seek immediate gratification. But turning down a reasonable offer in order to proceed with trial appears to contradict that expectation. However, if we conceive of the gratification as being the risky behavior itself as distinct from the ultimate outcome, then the reckless behavior makes sense.

Accepting a settlement would actually deprive the reckless litigator of the dopamine/serotonin rush that continued battle provides. The game itself—the anticipation—is the reward.[30] Winning and losing are secondary, important as they may well be. Lombardi had it wrong—at least for reckless litigators. Winning isn’t everything. It certainly isn’t the only thing. It is the second or third thing.[31]

We might call this feel-good litigating. In the language of classical economics, the utility function for reckless litigators looks different from that of normal litigators. They get marginally more satisfaction out of the risk (= thrill) than from the reward. Put differently, for them an eventual win is frosting that they did not expect anyway. (They are not stupid.) Since it is such a long shot, they might as well get the dopamine/serotonin hit from going for it, which the subconscious neurosystem “prefers” to the paltry reward of selling the claim to the defendant now for a discounted value.

The same mechanism might be at work with the lottery. Everyone knows that the odds are impossibly long. But everyone also knows that someone eventually wins. (No one would play if losing were an absolute certainty.) For a small price ($1 or $2), they can get a temporary hit of dopamine/serotonin. In some ways, it is no different from paying $2 for an ice cream cone. If people expected to win, then playing the lottery would be irrational. As a means for satisfying a need for increased dopamine/serotonin, it is not irrational at all. (Remember, this occurs at a subconscious level; the conscious brain is not aware of nor can it access these processes.)

Could it be that the unexpectedness of events (the surprise factor) in high-stakes litigation gives some lawyers the reward they crave that leads them to take risks not calculated to pay off (i.e., irrational risks)?[32]

With respect to the reckless litigator phenomenon, the neurological research so far gives rise to the following hypothesis:

Smart people do dumb things because their neurotransmitter systems incline them to impulsive and risky behavior. They can’t help themselves.[33]

But I suspect that other aspects of cognitive functioning also come into play with the reckless litigator, some of which I will summarize in the following two sections.

Cognitive Myopia Exacerbates the Reckless Litigator Phenomenon

Over the past 35 years, numerous psychologists and economists have investigated a series of cognitive biases and heuristics that affect the quality of our decisions. Of the many biases and heuristics that scientists have isolated, four are particularly relevant to the reckless litigator phenomenon: Overconfidence bias, confirming evidence bias, availability heuristic, and acceptability heuristic.

I’m Better Than I Think I Am: The Overconfidence Bias

A large body of research has established that we not only make predictions that turn out to be wrong—I’ll be

home by 6:00; the trial will take only three days; the project will cost no more than $250,000—but in many cases, we are highly confident that our predictions are right--a confidence that is not justified by our track record.

The problem is not limited to everyday affairs; it plagues professionals across the board: physicians and nurses,[34] auditors,[35] college professors, [36] professional traders,[37] investment bankers,[38] political scientists,[39] and . . . drum roll, please . . . lawyers.[40] Yes, dear reader, I know it comes as a shock, but we lawyers are no better than anyone else when it comes to being unrealistically enamored of our own judgments about our predictions. We mispredict and, what is more important, we are more confident in the accuracy of our predictions than we should be. The discrepancy between our degree of accuracy and our level of confidence in our predictions is called “the overconfidence bias.”

As a result of overconfidence, we fail to search for additional evidence that might lead to different conclusions,[41] disregard evidence that contradicts currently held positions,[42] and refuse to use or give credence to corrective feedback.[43]

Our overconfidence is “most extreme with tasks of great difficulty.”[44] The harder the prediction task, such as forecasting the outcome of a complex antitrust case, the more likely we are to be overconfident. Judgment accuracy declines as the task becomes more difficult, but confidence does not.

This last point is particularly important when considering the reckless litigator. Already awash in dopamine, serotonin, and testosterone, the reckless litigator does not realize that properly assessing the complex case is beyond the powers of his unassisted brain. Now, add to this the finding that inexperienced people are less aware of their relative degree of incompetence compared with more experienced,[45] and the challenges to rational settlement decisions only increase.

Exactly What I Expected: The Confirming Evidence Bias

Our brains continuously build and test hypotheses about the way things are. Having settled on a belief, however, we like to hang on to it. Almost 400 years ago, Francis Bacon put it like this:” The human understanding, when it has once adopted an opinion, . . . draws all things else to support and agree with it. And though there be a greater number and weight of instances to be found on the other side, yet these it . . . neglects and despises.”[46] It’s like the old joke, “My mind’s made up; don’t confuse me with facts.”

But litigators are supposed to let the facts unmake their minds, at least until they reach a synthesis that adequately explains all available evidence. And, of course, they do . . . for the most part. Lawyers are professionals after all. It makes sense to keep an open mind; otherwise, we are likely to be blind-sided by the facts we have ignored. But litigators are also human; and humans can be pigheaded on occasion—or overconfident. What is true of litigators generally is doubly true of the reckless litigator.

The expression “Confirmation Bias” refers to our tendency to seek out evidence that confirms an existing belief, notion, theory, or hypothesis and to neglect contradictory evidence. [47] This bias is self confirming in that the more evidence we assemble in support of our belief, the more firmly we hold that belief and the less inclined we are to look for or consider contrary evidence.

Not only do we subconsciously pick and choose the evidence that supports our existing belief; but we erect barriers to contrary evidence, charging high entrance fees, demanding extraordinarily convincing proof. In the inimitable words of Cordelia Fine, “The brain evades, twists, discounts, misinterprets, even makes up evidence—all so that we can retain that satisfying sense of being in the right. . . . Even the most hastily formed opinion receives undeserved protection from revision.”[48]

As Bacon and others as far back as Thucydides[49] have noted, we become wedded to our beliefs, presumably

because they are our beliefs. When we have a dog in the fight, this tendency becomes even more pronounced. We become partisan perceivers, assiduously selecting only that which confirms what we already believe. All of this takes place subconsciously. At a conscious level, we appear to ourselves as . . . well, “fair and balanced.”[50]

Litigators are in the business of one-sided case-building, which means that we are sitting ducks for the confirmation bias, unwittingly molding facts to fit our theory of the case. And the confirmation bias contributes to our overconfidence when predicting outcomes.

Whatever Pops Into My Mind: The Availability Heuristic

Which occurs more often in the United States, death by shark attack or from falling airplane parts? Do more Americans die from diabetes and stomach cancer or from homicide and car accidents? Which is the more frequent killer, lightening or tornadoes? If you answered sharks, homicide and car accidents, and tornadoes, then you agree with the vast majority of people who answer these questions in controlled experiments, all of whom are wrong. 30 Americans are killed by falling airplane parts to every 1 who is dispatched by a shark. Diabetes and stomach cancer claim more victims than homicides and car accidents. And lightening sends many more people to an early death than do tornadoes.[51]

People who give the wrong answer are not stupid or even necessarily ignorant. They are merely making use of what social scientists call the availability heuristic, a tendency to base our probability estimates or explanations on the ease with which we can retrieve information. That which is sitting ready and waiting to be surfaced from our memory—because it is emotionally vivid or otherwise salient—becomes the likely explanation.

The availability heuristic is like a third-grade teacher who calls on the boy in the fourth row waiving his hand in the air, when the pensive girl in the back who did the homework actually knows the answer. The boy literally sticks out, while the girl is not noticed.

In the litigation setting, the availability heuristic combines with the confirmation bias to throw us off when we are making predictions about the likely outcomes of key decisions in the case. When assessing whether a judge is likely to deny a motion for summary judgment, we remember the fact that the judge rarely grants such motions and may overlook the fact that an unbiased view of the evidence leads to the conclusion that there are no material facts in dispute. When defending a personal injury suit against a truck company, the saliency of plaintiff’s drunken state at the time of the accident may subconsciously lead us to put less weight on the fact that his inebriation did not contribute to the accident.[52]

Loftus and Wagenaar speculated that the ready availability to our subconscious of wins and the suppression of losses might help fuel overconfidence.[53]

Accountability and the Acceptability Heuristic

Imagine how the same lawyer would respond in the following three settings:

The same lawyer would provide significantly different responses to each of these scenarios. At the CLE seminar, the lawyer would provide an on-the-one-hand-and-then-on-the-other-hand balanced analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the respective parties’ claims and defenses based on her expert knowledge of the law. The same lawyer responding to the partner about the viability of the complaint on behalf of a prospective (paying) client would provide a balanced opinion that stressed the strengths of the putative plaintiff’s case. Finally, the same lawyer would answer the client by predicting that they would ultimately win, notwithstanding some of the weaknesses in the case.[54]

How do I know this? For one thing, I've been there and done that. More seriously, however, this is what 30 years of research into the accountability effect tells us is likely to happen in circumstances like those set forth in these three scenarios.

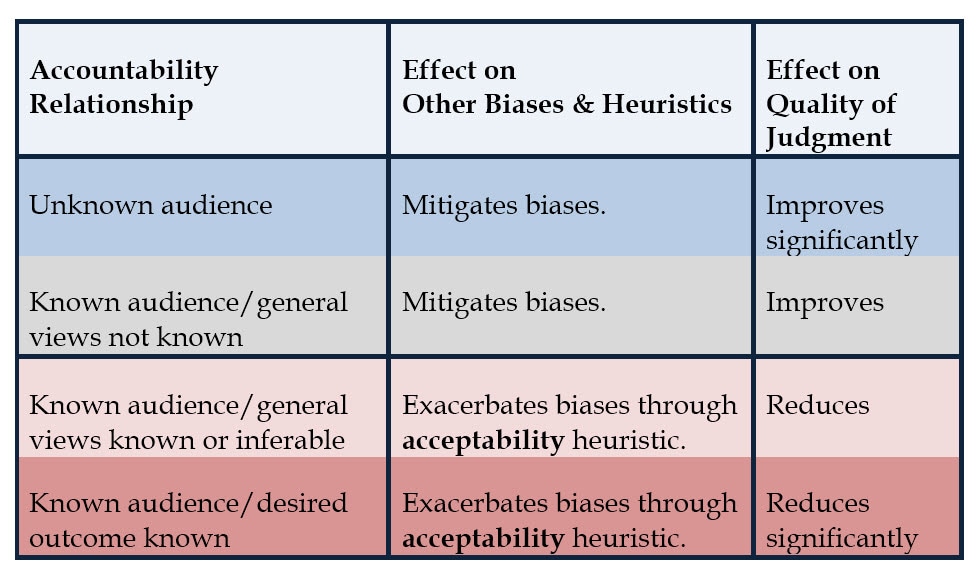

With respect to predictive judgments, when we know nothing about the views of the audience to whom we are accountable, we tend to engage in careful, balanced analyses and to render opinions in the nature of law school exam answers or law review articles.[55]

When we know the identity of the audience (a senior partner, a government agency, a prospective client) to whom we are accountable and can infer but do not know explicitly which outcome that audience prefers, then our predictions will be biased toward the outcome we think the audience wants to hear.

When we know both the identity and the preferred outcome of the audience to whom we are accountable, then we take the least care with our judgment and typically make predictions that conform to the views of the audience.[56]

When social scientists began researching the accountability effect, they assumed that having an accountability relationship would tend to mitigate overconfidence, confirming evidence, availability, and other heuristics and biases that distort judgment. The reasoning was that being accountable would move the responder away from reflexive thinking at the subconscious level to analytical thinking at the conscious level. Instead of making snap judgments, we would use decision-making processes that we can justify and demonstrate in a step-by-step fashion—much like a legal memorandum or judicial opinion.

Social scientists found that the accountability relationship, indeed, has this effect, but only if the audience is unknown or the views of the audience are unknown and cannot be readily inferred. Thus, scholars writing for peer-reviewed journals tend to write what they will be able to justify regardless of the views of particular scholars in their discipline.

As scientists conducted more research, they discovered that the exact opposite occurs when the accountable person knows what her audience wants to hear. It is not that we consciously turn into sycophants, obsequiously pandering to our clients’ wishful thinking (although that has been known to happen). Not at all. We sincerely believe that we are giving our best, objective, professional opinions.

Instead, what happens is that we skip the careful analysis we would perform if we were unaware of the views of those who will eventually see the opinion and whose acceptance we value or to whom we feel accountable in some way (fellow lawyers, members of a scholarly discipline, the public at large, etc.). We unwittingly rely on a heuristic—a fast and frugal opinion generator—to reach the answer. Philip Tetlock calls it “the acceptability heuristic.”[57]

Appraisers don't literally ask clients what value they need to come up with in the appraisal. They don't have to. An appraiser hired by the bank to prepare a report on the value of the house will know what the loan amount is and will have an indication of what value she needs to come up with. She doesn't have to think about this consciously. It just happens. It’s the acceptability heuristic at work.[58]

Similarly, lawyers know how to interpret the law to make it fit what the client wants to do. The most well-known recent example of this is the infamous torture memo written by John Yoo and Jay Bybee that put a legal blessing on waterboarding.[59] Auditors are not immune either, as the creative accounting of Arthur Andersen for Enron demonstrated. And appraisers, asked to take a “second look,” have been known to revise appraisals in ways that are more acceptable to the bank or client.

The work product of Professor Yoo and Judge Bybee may have been another instance of the acceptability heuristic at work. Not only did they know what the client wanted (to have legal cover for “enhanced interrogations”); but they were writing in a climate of fear and anxiety about possible additional terrorist attacks. They did not need consciously to bend their professional judgment to fit the desired outcome of their client; the subconscious acceptability heuristic did that job for them—as it does for us.[60]

We readily see the mote in our brother’s eye but are oblivious to the log in our own.[61] Others obviously slant their opinions to fit the views of their paying clients, but we would never stoop to anything so unprofessional or unethical.

But we know what our client would like us to say when they ask about their chances of success at trial. Because we know, the acceptability heuristic is likely to make us more susceptible to the confirmation bias and to increase our overconfidence.

Equally distressing is the client’s skewed expectation. Lay clients and those who have only one significant case in their lifetimes might expect that their lawyer will give them good news. After all, the client is paying her to win. She doesn’t want to hear bad news. Indeed, a lawyer who predicted a loss might be fired and told, “I want a lawyer who believes in our case and will fight to win.”

The Problem: Chasing Longshots

Over 95% of all lawsuits are resolved by agreement—before any verdict is rendered; but with hundreds of thousands of lawsuits pending at any given moment, tens of thousands of trials occur in state and federal courts every year. Recent research by Randall Kiser and others.[1] provides conclusive evidence that many parties erroneously reject settlement proposals, obtaining significantly worse results at trial, but nevertheless convincing themselves that it was something other than their own decision or incompetence that led to the disastrous outcome.[2]

Consider the following stories:

In 1949, Nick “the Greek” Dandalos and Johnny Moss sat down to a game of five-card stud at Binion’s Horseshoe in Las Vegas. In one legendary hand, Dandalos bet $50,000 on the chance—less than 7%—of drawing a Jack as his last card, which, amazingly, he did. Having computed the odds against the Greek’s having a Jack in the hole, Moss shoved in another $200,000 only to learn that his opponent had lucked out. The Greek won $250,000 in that one hand. When the game ended after several months of ‘round-the-clock play, however, Moss walked away with over $2.5 million of the Greek’s money. As Moss later put it, he had “figured the Greek for a chaser—playing hunches instead of the cards—and he used that insight to drain the Greek’s bankroll.”[3]

Shortly after becoming general manager of futures markets at Barings Bank in 1992, Nick Leeson began making unauthorized speculative trades in large amounts. At first, these trades went well, earning the bank significant profits and Leeson substantial bonuses. When the trades started failing, Leeson at first used an error account to hide his losses, which came to over £2 million. By the end of 1994, the losses exceeded £204 million. When Leeson fled Singapore in February of the following year, the losses had climbed to £827 million, twice the bank’s trading capital, a loss large enough to bring down the oldest merchant bank in London (1762 to 1995).[4]

In February 1994, eight members of a rescue team, having just saved three adventurers in Pincher Creek (Canada), were on their way back to home base when one of their number challenged Lane McGlynn to a game of hammer-heading, a race to see who can reach the highest point of the mountain on his snowmobile. Knowing the dangers of an avalanche in this area, the commander of the rescue team had expressly prohibited any hammer-heading before he sent the team on its rescue mission. Nevertheless, 21-year old McGlynn took off almost instantly upon hearing the dare. After his snowmobile came to a halt, the other party to the bet followed, presumably wanting to see if he could make it further up the hill. Shortly after he started, however, the snow broke loose, starting a massive avalanche, which eventually killed McGlynn and one other rescuer who was unable to start his snowmobile in time to get out of the way.[5]

A little over three weeks were left before the scheduled beginning of the trial of Anderson et al. v. Cryovac et al., the Woburn, Massachusetts toxic tort case made famous in A Civil Action. The judge having urged the parties to get serious about settlement, Jan Schlichtmann and his partners decided to demand $175 million, hoping to end the haggling at around $100 million. The lawyers gathered in an opulent conference room at the Boston Four Seasons for the settlement showdown. After Schlichtmann finished his introductory remarks, James Gordon, the firm’s financial advisor, laid out the plaintiffs’ demand: $1.5 million for each of the eight plaintiffs for 30 years plus $25 million cash now plus another $25 million to establish a foundation to study toxic poisoning through groundwater pollution—altogether, $410,000,000. Jerry Facher, representing Beatrice Foods, remarked, “If I wasn’t being polite, I’d tell you what you could do with this demand.” After Schlichtmann answered a few questions from Bill Cheeseman, the lead attorney for W.R. Grace, Facher packed up his brief case, stuffed a croissant in his pocket, and walked out. Cheeseman and his team quickly followed. The entire negotiation had lasted 37 minutes. The case went to trial, and Schlichtmann ultimately declared bankruptcy.[6]

And then there was the defense team in John Edwards’s last big case, Lakey v. Sta-Rite, involving a young plaintiff who would need continual medical care and numerous surgeries during much, if not all, of her remaining life. Shortly before trial, after all other defendants had settled for slightly more than $5 million, Sta-Rite rejected the plaintiffs’ settlement demand of $4.7 million, offering only $100,000. Three weeks later, the jury returned a $25 million verdict in compensatory damages alone with the punitive damages phase yet to come. At this point, Sta-Rite agreed to settle for the jury verdict.[7]

These stories (and others that could be added from auditing, medicine, and other fields) have one thing in common: The principal players acted impulsively, taking chances a rational analysis would reveal as foolhardy.[8] Nick the Greek bet over $50,000 (in 1949!) on the 7% chance that a Jack would turn up on his last card. The snowmobilers risked triggering an avalanche after having been ordered not to do any hammer-heading. Schlichtmann let unadulterated avarice mixed with a heavy dose of moral outrage cloud his thinking to an extent that he blew up any chance of a pre-trial settlement. (Facher and Cheeseman were not behaving in the most rationally responsible way either.) And the defense in the Sta-Rite case bet its $22.5 million insurance policy that John Edwards, who had racked up $125,000,000 in settlements and verdicts in the 15 previous years, didn’t know what he was doing.

The phenomenon on display in all of these examples was dramatized in the movie, Tin Cup. The protagonist (Tin Cup), a golfer with superb technique who ekes out a living as a driving range pro, needlessly takes risky chances in important games. Self-control eludes him. In the climax of the movie, Tin Cup blows his chance to win the U.S. Open by repeatedly and unnecessarily trying to hit a 250 yard shot with a 3 wood over water onto a postage-stamp green, finally succeeding—and scoring a 12 on the hole.

What is going on when lawyers throw caution to the wind, refusing reasonable buyouts and going for broke on the longest of long shots? What explains the “reckless litigator?” Among the many possible explanations for this kind of behavior, a few candidates derived from neurology and cognitive science merit particular attention, providing clues about why the reckless litigator—notwithstanding his fiduciary duty to his client—poses a special challenge to a rational adversary.

The Diagnosis—“The Fault, Dear Brutus . . .”

There are many possible explanations of the reckless litigator syndrome (reckless gambler, reckless skier, reckless golfer, etc.), the most obvious being simply that the lawyer does not have a good grasp of the law or evidence or both respecting the case at hand. While that theory would explain some negotiation decision errors, i.e., the failure to properly assess the value of the case based on probable outcomes, it would not cover all instances of negotiation decision errors in the settlement context. As Jan Schlichtmann’s settlement decisions in A Civil Action illustrate, some highly competent lawyers—lawyers who know the law inside out and are thoroughly immersed in the evidence—behave recklessly in high-stakes bargaining contexts.

Research on cognitive biases and heuristics together with recent developments in the field of Neureconomics suggest that at least part of the “fault, dear Brutus, lies in ourselves” or, more accurately, in the neurophysiological makeup of the reckless litigator's brain. The following discussion summarizes some of the results of this research as it applies to the reckless litigator phenomenon.[9]

Hopped Up on Dopamine, Serotonin, and Testosterone

Extrapolating from the extensive research on loss aversion,[10] we can assume that given the choice between accepting a settlement proposal of $200,000 and proceeding to trial with a 1/3 chance of winning $600,000 (and a 2/3 chance of nothing), about 70-80% of us will take the $200,000. Much of the scholarly discussion on loss aversion focuses on the choice that most of us--the 70-80%--make. We choose to avoid losses. But some of us—including reckless litigators—take the other path. We go for it. We engage in risk-seeking behavior. “Hey, a 1/3 chance at $600,000 sounds like a pretty good deal.”

This predisposition to risk-seeking is further buttressed in the settlement context by the endowment effect—our tendency to demand more when we sell an object than we would pay if we were buying it.[11] In the settlement context, we value the same case more if we are the seller (plaintiff) than if we are the buyer (defendant).[12]

As the seller, the plaintiff sees the case as having much greater value than does the buyer/defendant. The endowment effect creates a natural gap between plaintiff and defendant that must somehow be bridged.

But this effect is exacerbated with the reckless litigator, who harbors a subconscious need to go for it, much like Nick Dandalos, Nick Leeson, and the movie character Tin Cup.

Now comes a gaggle of scientists who are establishing a correlation between loss aversion/risk seeking and the genetic structure of our neurotransmitter systems. For example, the authors of one recently published study provide evidence that the amount of dopamine present in certain areas of the brain modulates the sensitivity towards the valuation of gains while the level of serotonin modulates the sensitivity towards valuation of losses.[13]

To function well, we need dopamine, for which our brains have special receptors called dopamine receptor genes. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that carries impulses between nerve cells, promoting increased feelings of alertness, wakefulness, assertiveness, and aggressiveness.[14] It is part of the brain’s reward system, helping to create the positive effects that various objects or conditions (food, sexual contact, warmth, drugs, etc.) have on the individual.[15]

Most of us have four repetitions (alleles) of the receptor gene D4 (DRD4), which means that we don’t need all that much dopamine to get the job done. A little goes a long way. Some of us (the percentage varies by population) have seven alleles of D4, commonly referred to as DRD4.7. Those people need more dopamine to get the same effect that the standard D4’s get with less.

A considerable body of research has established a correlation between the dopamine receptor D4.7 (the long form of D4) and risk-seeking behavior. Apparently, such activity stimulates the increased production of dopamine that D4.7’s need for brain processes that control a variety of functions, including the ability to experience pain and pleasure. Researchers have established correlations between D4.7 and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder,[16] pathological gambling,[17] behavioral disinhibition,[18] financial risk taking in men,[19] alcoholism,[20] early sexual activity,[21] impulsivity,[22] and long-range migration.[23]

Related research has looked at the correlation of long forms of serotonin receptor genes with risk-related behavior.[24]

A recent study found that repeat functional polymorphism in the Monoamine Oxidase A Gene is associated with a preference for long-shot lotteries and reduced purchasing of insurance—the behavior profile of the reckless litigator.[25] Like the studies of dopamine and serotonin, the risk-seeking behavior correlates with an unusual (long) form of the gene.

And, of course, there is also the testosterone factor, which is why I’ve been using the pronoun “he” when referring to the reckless litigator. Several researchers have found a correlation between testosterone levels and risk-seeking behavior.[26] One study of risk taking on a London trading floor found that a trader’s morning testosterone level predicts his day’s profitability, and the persistence of acutely elevated steroids may shift risk preferences, affecting a trader’s ability to engage in rational choices.[27]

Scientists and scholars in the emerging field of Neureconomics[28] are pulling these and other findings about brain function together into theories about risk aversion and atypical risk-seeking (a/k/a novelty seeking) that are augmenting and enhancing Prospect Theory, which is a cornerstone of behavioral economics and contrasts with classical expected utility theory.[29]

Playing the game is more neurochemically rewarding than winning. Put differently, the reckless litigator needs the increased risk to generate the amount of dopamine/serotonin that most of us get from less risky behavior, just as a person with impaired hearing must turn up the volume to hear what others hear at lower volume.

There is a paradox related to the Reckless Litigator Syndrome. If we think of him as impulsive, then we would expect that he is predisposed to seek immediate gratification. But turning down a reasonable offer in order to proceed with trial appears to contradict that expectation. However, if we conceive of the gratification as being the risky behavior itself as distinct from the ultimate outcome, then the reckless behavior makes sense.

Accepting a settlement would actually deprive the reckless litigator of the dopamine/serotonin rush that continued battle provides. The game itself—the anticipation—is the reward.[30] Winning and losing are secondary, important as they may well be. Lombardi had it wrong—at least for reckless litigators. Winning isn’t everything. It certainly isn’t the only thing. It is the second or third thing.[31]

We might call this feel-good litigating. In the language of classical economics, the utility function for reckless litigators looks different from that of normal litigators. They get marginally more satisfaction out of the risk (= thrill) than from the reward. Put differently, for them an eventual win is frosting that they did not expect anyway. (They are not stupid.) Since it is such a long shot, they might as well get the dopamine/serotonin hit from going for it, which the subconscious neurosystem “prefers” to the paltry reward of selling the claim to the defendant now for a discounted value.

The same mechanism might be at work with the lottery. Everyone knows that the odds are impossibly long. But everyone also knows that someone eventually wins. (No one would play if losing were an absolute certainty.) For a small price ($1 or $2), they can get a temporary hit of dopamine/serotonin. In some ways, it is no different from paying $2 for an ice cream cone. If people expected to win, then playing the lottery would be irrational. As a means for satisfying a need for increased dopamine/serotonin, it is not irrational at all. (Remember, this occurs at a subconscious level; the conscious brain is not aware of nor can it access these processes.)

Could it be that the unexpectedness of events (the surprise factor) in high-stakes litigation gives some lawyers the reward they crave that leads them to take risks not calculated to pay off (i.e., irrational risks)?[32]

With respect to the reckless litigator phenomenon, the neurological research so far gives rise to the following hypothesis:

Smart people do dumb things because their neurotransmitter systems incline them to impulsive and risky behavior. They can’t help themselves.[33]

But I suspect that other aspects of cognitive functioning also come into play with the reckless litigator, some of which I will summarize in the following two sections.

Cognitive Myopia Exacerbates the Reckless Litigator Phenomenon

Over the past 35 years, numerous psychologists and economists have investigated a series of cognitive biases and heuristics that affect the quality of our decisions. Of the many biases and heuristics that scientists have isolated, four are particularly relevant to the reckless litigator phenomenon: Overconfidence bias, confirming evidence bias, availability heuristic, and acceptability heuristic.

I’m Better Than I Think I Am: The Overconfidence Bias

A large body of research has established that we not only make predictions that turn out to be wrong—I’ll be

home by 6:00; the trial will take only three days; the project will cost no more than $250,000—but in many cases, we are highly confident that our predictions are right--a confidence that is not justified by our track record.

The problem is not limited to everyday affairs; it plagues professionals across the board: physicians and nurses,[34] auditors,[35] college professors, [36] professional traders,[37] investment bankers,[38] political scientists,[39] and . . . drum roll, please . . . lawyers.[40] Yes, dear reader, I know it comes as a shock, but we lawyers are no better than anyone else when it comes to being unrealistically enamored of our own judgments about our predictions. We mispredict and, what is more important, we are more confident in the accuracy of our predictions than we should be. The discrepancy between our degree of accuracy and our level of confidence in our predictions is called “the overconfidence bias.”

As a result of overconfidence, we fail to search for additional evidence that might lead to different conclusions,[41] disregard evidence that contradicts currently held positions,[42] and refuse to use or give credence to corrective feedback.[43]

Our overconfidence is “most extreme with tasks of great difficulty.”[44] The harder the prediction task, such as forecasting the outcome of a complex antitrust case, the more likely we are to be overconfident. Judgment accuracy declines as the task becomes more difficult, but confidence does not.

This last point is particularly important when considering the reckless litigator. Already awash in dopamine, serotonin, and testosterone, the reckless litigator does not realize that properly assessing the complex case is beyond the powers of his unassisted brain. Now, add to this the finding that inexperienced people are less aware of their relative degree of incompetence compared with more experienced,[45] and the challenges to rational settlement decisions only increase.

Exactly What I Expected: The Confirming Evidence Bias

Our brains continuously build and test hypotheses about the way things are. Having settled on a belief, however, we like to hang on to it. Almost 400 years ago, Francis Bacon put it like this:” The human understanding, when it has once adopted an opinion, . . . draws all things else to support and agree with it. And though there be a greater number and weight of instances to be found on the other side, yet these it . . . neglects and despises.”[46] It’s like the old joke, “My mind’s made up; don’t confuse me with facts.”

But litigators are supposed to let the facts unmake their minds, at least until they reach a synthesis that adequately explains all available evidence. And, of course, they do . . . for the most part. Lawyers are professionals after all. It makes sense to keep an open mind; otherwise, we are likely to be blind-sided by the facts we have ignored. But litigators are also human; and humans can be pigheaded on occasion—or overconfident. What is true of litigators generally is doubly true of the reckless litigator.

The expression “Confirmation Bias” refers to our tendency to seek out evidence that confirms an existing belief, notion, theory, or hypothesis and to neglect contradictory evidence. [47] This bias is self confirming in that the more evidence we assemble in support of our belief, the more firmly we hold that belief and the less inclined we are to look for or consider contrary evidence.

Not only do we subconsciously pick and choose the evidence that supports our existing belief; but we erect barriers to contrary evidence, charging high entrance fees, demanding extraordinarily convincing proof. In the inimitable words of Cordelia Fine, “The brain evades, twists, discounts, misinterprets, even makes up evidence—all so that we can retain that satisfying sense of being in the right. . . . Even the most hastily formed opinion receives undeserved protection from revision.”[48]

As Bacon and others as far back as Thucydides[49] have noted, we become wedded to our beliefs, presumably

because they are our beliefs. When we have a dog in the fight, this tendency becomes even more pronounced. We become partisan perceivers, assiduously selecting only that which confirms what we already believe. All of this takes place subconsciously. At a conscious level, we appear to ourselves as . . . well, “fair and balanced.”[50]

Litigators are in the business of one-sided case-building, which means that we are sitting ducks for the confirmation bias, unwittingly molding facts to fit our theory of the case. And the confirmation bias contributes to our overconfidence when predicting outcomes.

Whatever Pops Into My Mind: The Availability Heuristic

Which occurs more often in the United States, death by shark attack or from falling airplane parts? Do more Americans die from diabetes and stomach cancer or from homicide and car accidents? Which is the more frequent killer, lightening or tornadoes? If you answered sharks, homicide and car accidents, and tornadoes, then you agree with the vast majority of people who answer these questions in controlled experiments, all of whom are wrong. 30 Americans are killed by falling airplane parts to every 1 who is dispatched by a shark. Diabetes and stomach cancer claim more victims than homicides and car accidents. And lightening sends many more people to an early death than do tornadoes.[51]

People who give the wrong answer are not stupid or even necessarily ignorant. They are merely making use of what social scientists call the availability heuristic, a tendency to base our probability estimates or explanations on the ease with which we can retrieve information. That which is sitting ready and waiting to be surfaced from our memory—because it is emotionally vivid or otherwise salient—becomes the likely explanation.

The availability heuristic is like a third-grade teacher who calls on the boy in the fourth row waiving his hand in the air, when the pensive girl in the back who did the homework actually knows the answer. The boy literally sticks out, while the girl is not noticed.

In the litigation setting, the availability heuristic combines with the confirmation bias to throw us off when we are making predictions about the likely outcomes of key decisions in the case. When assessing whether a judge is likely to deny a motion for summary judgment, we remember the fact that the judge rarely grants such motions and may overlook the fact that an unbiased view of the evidence leads to the conclusion that there are no material facts in dispute. When defending a personal injury suit against a truck company, the saliency of plaintiff’s drunken state at the time of the accident may subconsciously lead us to put less weight on the fact that his inebriation did not contribute to the accident.[52]

Loftus and Wagenaar speculated that the ready availability to our subconscious of wins and the suppression of losses might help fuel overconfidence.[53]

Accountability and the Acceptability Heuristic

Imagine how the same lawyer would respond in the following three settings:

- At a continuing education seminar, an audience member presents a set of facts to a lawyer well-versed in antitrust law and asks for her opinion on the viability of a complaint on those facts.

- A partner of the same lawyer comes to her with the same facts, noting that the firm has been asked to represent party A (a paying client) in an antitrust case against party B (a deep pocket), and asks for her opinion about the viability of a lawsuit by A against B.

- The lawsuit having been filed and discovery well underway, the client asks the same lawyer for her prediction on the likelihood that they will win the lawsuit.

The same lawyer would provide significantly different responses to each of these scenarios. At the CLE seminar, the lawyer would provide an on-the-one-hand-and-then-on-the-other-hand balanced analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the respective parties’ claims and defenses based on her expert knowledge of the law. The same lawyer responding to the partner about the viability of the complaint on behalf of a prospective (paying) client would provide a balanced opinion that stressed the strengths of the putative plaintiff’s case. Finally, the same lawyer would answer the client by predicting that they would ultimately win, notwithstanding some of the weaknesses in the case.[54]

How do I know this? For one thing, I've been there and done that. More seriously, however, this is what 30 years of research into the accountability effect tells us is likely to happen in circumstances like those set forth in these three scenarios.

With respect to predictive judgments, when we know nothing about the views of the audience to whom we are accountable, we tend to engage in careful, balanced analyses and to render opinions in the nature of law school exam answers or law review articles.[55]

When we know the identity of the audience (a senior partner, a government agency, a prospective client) to whom we are accountable and can infer but do not know explicitly which outcome that audience prefers, then our predictions will be biased toward the outcome we think the audience wants to hear.

When we know both the identity and the preferred outcome of the audience to whom we are accountable, then we take the least care with our judgment and typically make predictions that conform to the views of the audience.[56]

When social scientists began researching the accountability effect, they assumed that having an accountability relationship would tend to mitigate overconfidence, confirming evidence, availability, and other heuristics and biases that distort judgment. The reasoning was that being accountable would move the responder away from reflexive thinking at the subconscious level to analytical thinking at the conscious level. Instead of making snap judgments, we would use decision-making processes that we can justify and demonstrate in a step-by-step fashion—much like a legal memorandum or judicial opinion.

Social scientists found that the accountability relationship, indeed, has this effect, but only if the audience is unknown or the views of the audience are unknown and cannot be readily inferred. Thus, scholars writing for peer-reviewed journals tend to write what they will be able to justify regardless of the views of particular scholars in their discipline.

As scientists conducted more research, they discovered that the exact opposite occurs when the accountable person knows what her audience wants to hear. It is not that we consciously turn into sycophants, obsequiously pandering to our clients’ wishful thinking (although that has been known to happen). Not at all. We sincerely believe that we are giving our best, objective, professional opinions.

Instead, what happens is that we skip the careful analysis we would perform if we were unaware of the views of those who will eventually see the opinion and whose acceptance we value or to whom we feel accountable in some way (fellow lawyers, members of a scholarly discipline, the public at large, etc.). We unwittingly rely on a heuristic—a fast and frugal opinion generator—to reach the answer. Philip Tetlock calls it “the acceptability heuristic.”[57]

Appraisers don't literally ask clients what value they need to come up with in the appraisal. They don't have to. An appraiser hired by the bank to prepare a report on the value of the house will know what the loan amount is and will have an indication of what value she needs to come up with. She doesn't have to think about this consciously. It just happens. It’s the acceptability heuristic at work.[58]

Similarly, lawyers know how to interpret the law to make it fit what the client wants to do. The most well-known recent example of this is the infamous torture memo written by John Yoo and Jay Bybee that put a legal blessing on waterboarding.[59] Auditors are not immune either, as the creative accounting of Arthur Andersen for Enron demonstrated. And appraisers, asked to take a “second look,” have been known to revise appraisals in ways that are more acceptable to the bank or client.

The work product of Professor Yoo and Judge Bybee may have been another instance of the acceptability heuristic at work. Not only did they know what the client wanted (to have legal cover for “enhanced interrogations”); but they were writing in a climate of fear and anxiety about possible additional terrorist attacks. They did not need consciously to bend their professional judgment to fit the desired outcome of their client; the subconscious acceptability heuristic did that job for them—as it does for us.[60]

We readily see the mote in our brother’s eye but are oblivious to the log in our own.[61] Others obviously slant their opinions to fit the views of their paying clients, but we would never stoop to anything so unprofessional or unethical.

But we know what our client would like us to say when they ask about their chances of success at trial. Because we know, the acceptability heuristic is likely to make us more susceptible to the confirmation bias and to increase our overconfidence.

Equally distressing is the client’s skewed expectation. Lay clients and those who have only one significant case in their lifetimes might expect that their lawyer will give them good news. After all, the client is paying her to win. She doesn’t want to hear bad news. Indeed, a lawyer who predicted a loss might be fired and told, “I want a lawyer who believes in our case and will fight to win.”

Thus, the combination of the acceptability heuristic and the client’s transparent expectations can distort the predictive judgment considerably. This may be one reason why some lawyers hope that the mediator or early neutral evaluator will give the client a dose of reality. Some clients just do not want to hear that their claim against the dentist for improper dental work is not worth $2,000,000. After all, isn’t that what the woman with the hot cup of coffee got from McDonald’s?[62]

The Ego Game: Contending for Rank and Status

In the movie version of A Civil Action, while the jury is deliberating whether to dismiss Beatrice Foods from the case, the lawyer for Beatrice (Jerry Facher) makes a $20,000,000 settlement offer to Jan Schlichtmann in the hallway. Schlichtmann, desperate for money and his case against Beatrice in an extremely precarious position, turns it down. Shortly thereafter, the jury comes back, and Beatrice is out of the case. As third parties to this exchange, viewers realize that Schlichtmann has thrown away an opportunity to cover the ruinous expenses incurred to date as well as to build a war chest with which to continue the case against W.R. Grace.[63]

Among the factors blocking agreement at this point is Schlichtmann's own ego. He has become irrationally wedded to the righteousness of his cause and refuses to “give in” or “knuckle under” to Facher. If the jury decides against him, that is one thing. But if he takes Facher's offer, he will be one down in the personal competition game. Facher will have won. To accept any settlement with Beatrice at this time for any amount of money short of hundreds of millions of dollars would be tantamount to defeat. Having completely lost sight of his client's interests and even his own interest in financial survival, Schlichtmann refuses to bow to Facher. To paraphrase the famous line from The Godfather, what should be strictly business has become entirely personal.

Jockeying for rank and status in subtle and crude ways occupies a good part of our interaction energy. Remember the legendary encounter between Robin Hood and John Little at the log crossing the stream in Sherwood Forest?[64] They both come to the log at the same time, each from a different direction. Neither knows the other. Robin tells John to give way. John says, in effect, “Like hell I will. You back down.” Unable to resolve the matter with social conventions, they had a fight. Or, perhaps, that was the social convention at the time for settling such confrontations. John dumps Robin in the water and forces Robin to carry him across the stream.

That story is played out in numerous permutations around the globe every day. The instinct to behave this way was bequeathed by our evolutionary ancestors who engaged in what the late anthropologist Roger Gould has called a “Collision of Wills.” However, unlike most intraspecies fights for dominance, those of humans all-too frequently become deadly.[65] Honor cultures establish elaborate rituals around the dominance/subordination theme that occasionally require reciprocal retribution—revenge—for generations.

While the instinct to establish rank and status through dominance and subordination may serve good ends for the species as a whole, they are often counterproductive for individuals. In other words, we often get better results by finding other ways than fighting to resolve conflicts.

We all know this basic truth, yet we get caught up in fighting with each other, if not physically, than through different proxy forms. We push and push back. We resist cooperating with each other. In an honor culture, it is a sign of weakness or possibly even treason for a member of one camp to cooperate with someone from the opposing group. Some lawyers or their clients have a similar attitude about meeting peacefully with the other side. Thus, we find it difficult to disentangle and work reasonably with each other. (Because it has now become conventional, mediation is a face-saving, honor-preserving means of communicating to resolve a dispute without putting yourself one down in the rank and status game.)

At a status conference, the judge berates us for bickering with each other. For crying out loud! That's what a lawsuit is—a fight. It is counterintuitive to cooperate, to get along, to help each other. We are supposed to do worse than bicker. How can judges expect us to be nice to each other? Our clients don't.

Judges expect it for their own institutional reasons. It makes their lives less difficult, gives them less work to do. But they also believe it is the sensible, reasonable thing to do. Outsiders seldom think it makes sense for parties to be contending with each other when there are obvious gains to be had for each through cooperation. So we condemn the fights of others; and engage in them ourselves.

Some researchers believe that dominance rituals are conflict management devices developed to reduce the frequency of aggression and the probability of escalating violence.[66] Establishing rank actually reduces the overall level of violence in a group. But ambiguity about rank and status creates a combustible encounter. Roger Gould examined data relevant to this topic in great detail and concluded that uncertainty about who is where in the pecking order leads to conflict, sometimes even deadly violence:

What makes people angry enough to kill in these stories has as much to do with the little things adversaries say and do while struggling as with the things they are ostensibly struggling about. It is this sensitivity to process—to tone, demeanor, gestures or turns of phrase—that suggests that winning the fight matters at least as much to disputants as walking away with the material stakes. This is not to say that material or substantive stakes, when they exist, do not matter, but rather that, when they do play a role, this role diminishes in relative importance as the dispute continues, allowing symbolic grievances to pile up.[67]

Regardless of its role in producing survival fitness for the gene pool, the king-of-the-mountain game can pose significant problems in negotiating sensible settlements.

We lawyers don't start slugging each other in settlement conferences, of course—at least, not often. Rather, we unwittingly and, at times imperceptibly, engage in struggles to negotiate hierarchy. So do our clients. And occasionally we do this to the detriment of good deals that might otherwise be worked out.

The propensity to bargain over positions instead of pursuing our objective interests is closely tied both to struggles over social rank and to our sense of identity. In effect, the position we stake out becomes a surrogate for us. Giving up the position is tantamount to backing down, to putting ourselves in a one-down relationship to our opponent. This is why our culture has worked out a rather intricate positional bargaining dance, based on reciprocal concessions. If neither side gives way unilaterally, neither side loses rank or status with respect to the other. Wisely or foolishly, I assert a position and I won't “bid against myself” by moving before the other side has come up (or down) in response to my previous move.

Concern about status may also be why we are “insulted” by unreasonably high demands and low offers. They signal that we are fools or are insignificant nobodies who can be pushed around. In some neighborhoods, actions like that can get you shot. In the settlement context, they just kill the negotiations.[68]

Because it is counter-instinctual to cooperate with a perceived enemy, it requires a conscious effort to do something different. In the words of Robert McNamara, lesson number one is "Empathize with your enemy."[69]

The Perfect Storm

All of this may seem to be a lengthy way to answer the question posed at the outset: Why do some litigators disregard objective information, throwing caution to the wind, rejecting reasonable settlement offers, insisting on going down in a blaze of ignominy at trial? What explains the reckless litigator syndrome?

The short answer is that the reckless litigator is a hostage of neurochemistry, cognitive biases and heuristics, and a genetically based drive to contend for rank and status that undermine an objective assessment of the case and block reasonable settlement proposals. Thinking is further distorted by the heightened emotional context in which settlement negotiations typically occur.[70]

In short, the reckless litigator is the product of a perfect storm of mental processes to which he has little or no access. It is a predisposition—one that can be overcome, but only if the reckless litigator himself is aware of it and takes appropriate measures to counteract it.

If this assessment is true or even largely true, it has significant implications for the strategic behavior of lawyers on the other side of the table, a subject to which I turn in the final section of this essay. But first, a word from your malpractice carrier and the disciplinary board.

Ethics and Malpractice Issues

Like all attorneys in common law countries, litigators, being effectively trustees, have a fiduciary duty to subordinate their own interests to those of their clients.[71] It takes little imagination to see how the interests of the litigation lawyer can become entangled with those of the client, leaving us to wonder whose interests are really driving the judgment calls the lawyer makes.[72] It is common to hear non-lawyers express the assumption that lawyers pursue strategies that fatten their wallets when they could resolve the case if they chose to do so,[73] a view that finds superficial, though not real, support by the debate within the profession about the need to take more cases to trial.[74]

Lawyers bristle at the suggestion that they would put their own pecuniary interests ahead of their clients’ interests when providing advice and making judgment calls in litigation. Rightly so, in my experience. Heretofore, I have thought that only the unscrupulous—of which there are, as in any profession, alas, a few—would consciously prolong litigation or engage in other costly activity in order to make a college tuition payment or buy a boat.

Now, however, I wonder about the degree to which neurophysiology and subconscious biases coupled with the personal interests of lawyers could adversely affect the litigator’s disinterested behavior, thereby contributing to settlement failures and decision errors of even the most ethically fastidious. Do reckless litigators, in violation of their fiduciary duty, fail to resolve cases because they are so consumed by ego contests and the psychic satisfaction of playing the game that they lose the professional objectivity necessary to give the client rational settlement advice?

As noted at the outset, Randall Kiser has shown through extensive empirical evidence and analysis that about 61% of plaintiffs and 24% of defendants who reject settlement offers receive worse results at the conclusion of trial.[75] In such cases, the parties (or their attorneys or both) have made what Kiser calls “decision errors,” rejecting an offer that would have made them financially better off. If, as I have been trying to establish, the reckless litigator truly exists, then it is safe to assume that at least some of the decision errors in Kiser’s database were committed by reckless litigators—i.e., lawyers whose genetically programmed neurophysiology in concert with subconscious biases and heuristics predisposed them to seek the risky alternative to settlement.

In Beyond Right and Wrong, Kiser also provides a separate in-depth discussion of the ethical and malpractice implications of these decision errors.[76] The general proposition that a lawyer owes a duty to the client to provide competent advice in the settlement context is unassailable. As the New Jersey Supreme Court put the matter, “[W]e insist that the lawyers of our state advise clients with respect to settlements with the same skill, knowledge, and diligence with which they pursue all other legal tasks. Attorneys are supposed to know the likelihood of success for the types of cases they handle and they are supposed to know the range of possible awards in those cases.”[77]

The strictures of professional ethics contain no exceptions for those whose incompetence is caused by mental or physical aberrations. To the contrary, lawyers whose competence is impaired by some mental or physical condition are not permitted to practice law.[78] A fortiori, it is at least arguable that lawyers who engage in inordinate risk-seeking should somehow be reined in and not be permitted to damage their clients’ interests. (Of course, if it is the client that suffers from reckless litigator syndrome, that is another matter altogether.)

Responding to the Reckless Litigator: Some Possible Solutions

Of the many different ways to deal with the reckless litigator’s neurochemistry and cognitive impediments, the following six points sum up much of the sound advice:

1. Think strategically. Know your litigation and settlement goals, why you want to achieve them, and how you plan to go about doing that. Have a plan and adapt as necessary. Avoid letting the reckless litigator’s moves control your response by pushing you into reactive mode. In other words, respond in advance by devising a litigation plan, of which a settlement plan (strategy) is a subpart, that lets you be 3-4 moves ahead of your opponent, not one move behind.

In any negotiation, the wise strategist should always expect the other side to work towards a goal that is in that side’s perceived best interest.[79] (This does not mean that they will always negotiate optimally towards satisfying those interests. As we saw from the brief discussion of cognitive biases and heuristics, frequently their negotiation strategy will be sub-optimal.)

The problem with the reckless litigator is that his driving interest is not always monetary. It may be psychic-emotional—the rush he gets from the game itself regardless of the outcome. In other words, trying to address an interest that is not his dominant interest (money) may be frustrating; worse, it could lead the non-savvy negotiator to pay more (accept less) than she should to settle a case. (Presumably, even for the reckless litigator, there is some number that is high (low) enough to override the psychic-emotional reward he derives from the game, in exchange for which he will give up the game.)

2. Think analytically about the net present expected financial value[80] of your case. Break your case down into its component parts, estimate the probable values of each component, and compute their effects on the financial value of the case.[81] To avoid reacting to what the reckless litigator does, you must have a high degree of confidence in your estimate of its net present financial value (i.e., the net value of the final executed judgment discounted to the present). To achieve such confidence in complex litigation, use a trustworthy method and appropriate tools and techniques to supplement and correct your intuitive sense of case value. Where there is no method, demons come to dwell.

3. Be mindful of the reckless litigator’s mindlessness. By definition, the reckless litigator does not think strategically or analytically. It is a mistake to expect him to develop a rational analysis of the case. And, though understandable, it serves no purpose to fume about his failure to act rationally. This does not mean that he necessarily is oblivious to his or his client’s interests, but he is not likely to think through how best to satisfy them. More importantly, he may (unwittingly) put them second or third to his own psychic-emotional needs. Accordingly, your task is to figure out how to protect your client’s interests, which requires that you think about the reckless litigator’s interests as well.

4. Know your walkaway number and be prepared to walk. The reckless litigator’s preferred strategy is a game of chicken. Your walkaway number should be the net present expected financial value plus (minus) any premium (discount) for the dollar equivalent of other interests (avoiding bad publicity, avoiding the emotional cost of litigation, avoiding a possibly bad precedent, avoiding the diversion of executive time from more important matters, etc.). Thus, your walkaway number may be higher, lower, or equal to the net present expected financial value of the case for your side. But whatever it is, you must know the number at which your client’s interests are best satisfied and be prepared politely and firmly to say “game over” when you have reached that number.

Your walkaway number may be sufficiently large (small) to override the reckless litigator’s need for the psychic-emotional satisfaction of continued litigation. But if not, you should walk away. Don’t get sucked into paying more (accepting less) than the case is worth to you just because the opponent is a reckless litigator.

5. Develop and use tactics that respond specifically to the neurochemical and bias needs of the reckless litigator. For example, a mini trial may provide the thrill (and reality check) that the reckless litigator needs. And, paradoxically, the reckless litigator may be open to this option because it allows him to perform in a simulated game, receiving at least some of the psychic benefits of the real thing.

6. Be aware of your own biases and take appropriate steps to mitigate them. Everyone has subconscious biases that can interfere with rational thinking. The first line of defense is awareness. In short, make sure that you yourself are not the reckless litigator in this equation.

The Antidote to the Ego Game in the Negotiation Process